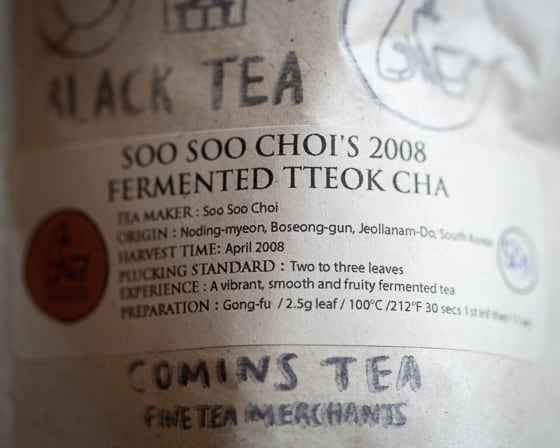

2008 Soo Soo Choi’s Tteok Cha from Comins Tea

Soo Soo Choi’s Tteok Cha (떡차) is the first Korean tea I’ve tried, and the first Korean Hei Cha (or Dark Tea) that I’ve tried. It is like no other Hei Cha that I’ve had before.

“Tteok” tea is processed similarly to a Korean rice cake of the same name. The rice cakes are usually used for dessert, and pressed into various shapes after being steamed or pounded.

To make ddok tea, fresh leaves were picked and selected, and then the leaves were steamed in an earthenware steamer. The cooked leaves were pounded to a pulpy mass, the pulp formed into little cakes, some as small as the size of a coin. To dry and store, cakes were pierced and strung together on a cord, like a string of copper cash.

These were pressed around 12 years ago, allowing them time to develop and mellow in flavour. The tea comes in a novel shape. They are like large coins. Each coin is around 10 grams, so I’ve been breaking them in half with a Puer pick, as a half is about right for my gaiwan.

Brewing is different from other compressed teas. These take some time to open up, and even after six or seven infusions are still holding their shape. I started with 30s for the rinse, and then 15s thereafter. The result is that the initial profile stays for some time.

This is also a different flavour than I’ve seen from fermented teas before. The Comins site describes it as vibrant, smooth and fruity. It isn’t a pronounced fruitiness, but there is definitely something there. It is also a very crisp and clean profile, rather than the more earthy flavours I usually associate with fermented teas.

After some research, it turns out that infusing the tea isn’t the usual way to brew Tteok Cha.

Tteok-cha was originally developed for use medicinally, and is brewed by decoction rather than by infusion. Preparation of the tea has two basic stages: roasting the tea over a charcoal fire, and then simmering it over heat for more than three hours.

Since ancient times, tteok-cha was toasted before brewing, using tongs of bamboo. The use of bamboo tongs to brown caked tea was recommended in the Book of Tea written in 780 A.D. by the tea master Lu Yü.

…

Heating the cake drove off excess moisture and further dried the tea, making it brittle when cooled. Exposure to heat also produced the Maillard reaction or browning, a chemical reaction between amino acids and sugars that determined flavor, aroma, and color.

My next challenge will be working out how to use the decoction method at home.